One route, by another name

In an age of tactical mastery, Route One football persists, but under a new guise

“Whichever team scores more goals usually wins.”

Iconic Pea and Ham Soup fan and ex-professional footballer Michael Owen’s knowledge of the game truly knows no bounds. This is the plainest statement about the game of football you will ever see. (Except for the implication that you sometimes don’t win if you score the most goals, but don’t think about that bit too much.)

When you break down the game to its barest concepts in attack, it’s all about who scores and how they score. The way or approach has changed over the decades and varied according to the desires of managers, the ability of players, and the style of the opposition

Ever since the massive success of Pep Guardiola at Barcelona - the beginning of the era of tiki-taka possessional football - a lot of people have gravitated towards the philosophy of positional play. While Pep wasn’t the creator of this concept (It had long been the base structure which Barcelona had aimed to play through, just with a different name, building off of Johan Cruyff’s Total Football) he did popularise it in the modern age, especially thanks to its use being mixed with the presence of Lionel Messi, arguably the greatest footballer ever.

The momentum of this notable style of play has, in turn, increased the number of articles and analysis on the subject, putting a large emphasis on playing out from the back in the current literature surrounding, and philosophical beliefs entrenched within, the game.

In recent years, very few top-level sides have stepped away from the ultimate aim of trying to score as many goals as possible (I say very few, because we all know those sides that just play for a draw most weeks).

Prompted by an expanding foreign influence and strategic revolutionaries, the degree of detail and analysis regarding tactics has reached an unprecedented level in England.

20 years ago, if you heard an English football fan utter the phrase “3-5-2”, they would’ve been referring to how many drinks they’d had at home, in the pub, and at half time. Nowadays they all either try to play like Pep’s Párvulo’s, or look to combat those sides by sitting back in deep-blocks and getting out quickly with slick passing movements on the break once the opposition lose the ball.

Accordingly, the long ball approach has become a largely old-fashioned and a secondary playing style. Long ball eschews the beauty of intricate passing play and coordinated counter-attacks for trial and error, as more often than not, the passes are headed out of play or kicked back down the field by the opposing team, caught by the keeper, or go out of bounds. The approach calls for tall, muscular center-forwards who can overpower defenders to win the ball. While the long ball can be very effective, particularly for teams of lesser technical ability, it traditionally has made for deadly dull viewing.

The practitioners of direct football, Jack Charlton’s Irish side of the late 80’s/early 90’s, or teams led by the likes of Sam Allardyce, Steve Bruce and Tony Pulis have ceased to exist, either passing on, retiring, or being forced to practice their ideas in the lower divisions of the football pyramid.

Sean Dyche’s Burnley were always awkward opponents; the last old-school major English side who played 4-4-2, made no attempt to dominate possession and were content to whack long balls downfield.

Burnley offered tactical variety to a league. They forced others out of their comfort zone, compelling them to excel at the physical, unfashionable side of the game.

It was always fascinating to see how bigger clubs handled Dyche’s “Brexit Ballers”. On one hand, they generally picked more physical players to fight fire with fire; on the other, they held possession longer to prevent the game becoming scrappy, pressed intensely to try to stop Burnley playing those long balls and held a particularly high defensive line to keep Dyche’s target man away from their goal.

They tell me now that the old days of Route-One Football are dead and gone.

In that case, I guess I’m seeing ghosts.

The Benefits of the Long Ball

“One must shed the bad taste of wanting to agree with many” ~ Friedrich Nietzsche

First of all, for the uninitiated, what is Route One football, and how does it benefit teams to play in this manner?

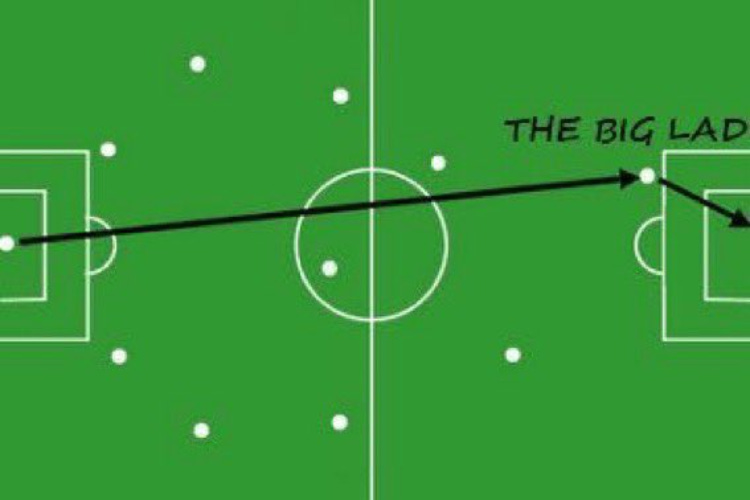

Many teams will concede that they have inferior levels of playing ability to some of their opposition, and so will see fit to ‘park the bus’. In a compact team, the gaps between each player will be small, so their opponents will find it difficult, not only to play passes that can penetrate their way in between these gaps, but will also struggle to find space to receive the ball between the defensive blocks, i.e between the defensive line and midfield line. One way in which the side in possession can break these lines, however, is by utilizing a target man.

The benefits of playing with a target player up front are also evident in counter-attacks. Often, a team’s counters will be built upon pacey wingers who can exploit the opposition’s defensive instability. However, there is also a place for physically imposing front men in counter-attacks. The best example of this that I’ve seen is probably Atletico Madrid’s use of Mario Mandzukic under Diego Simeone in the 2014/15 season.

Simeone prides himself on defensive organization combined with quick transitions into attack, and vice-versa. On a number of occasions that season, Atletico played quick and direct towards Mandzukic after turning over possession. The Croatian forward then used his strength to hold the ball up and allow his teammates time to get forward in support and laid it off to players like his support striker Antoine Griezmann, or just used their overpowering might to blast one home themselves.

Despite the stigma attached, even the most well respected managers in world football acknowledge the benefits of playing direct. Whether it be throwing a no-nonsense centre-back forward in search of an equaliser, playing over the opposition’s defensive lines rather than through them or catching the opponents out after a turnover in possession, the ‘long ball’ and the use of a target man certainly has its merits, and has really grown back into the game once again in the past few years.

There are a few that still follow the singular route to this day in the major leagues of European football, most notably in the Premier League, as Route One football has always been an almost uniquely Western European passion.

Sean Dyche may not be at his beloved Burnley anymore, but he’s still a devout worshipper at the altar of directness. His Everton side rank first in the league this season in terms of long passes attempted, with a total of 2248 at the time of writing, ar a rate of 64 per game. Dominic Calvert-Lewin has proved to be a hugely influential target man for the curry loving Northamptonshireman, when he’s been fit, as has the highly rated (by some very specific people) new signing from Udinese, Beto.

In first place on that list with 61 per game is Rob Edwards’ newly promoted Luton Town, who’ve needed to use the height and strength of players like Elijah Adebayo and Carlton Morris, alongside the pace of Irishman Chiedozie Ogbene up top to fight for as many points as they possibly can. At the time of writing, Luton have largely proved their doubters wrong this season, as they are the highest points scoring team of those that have been newly promoted thusfar.

The most significant amongst the users of the lengthy ball though is Thomas Frank’s Brentford. It’s clear this isn’t a new obsession for Brentford. They’ve long been a practitioner of “AVE IT” ball. This season they rank 6th in the league in terms of total long passes attempted, and 4th in long passes per game, but so far this is a down year for Brentford with the long pass as they’ve missed their key focal point to make the system tick perfectly on time, Ivan Toney, after he was found guilty of 232 breaches of the Football Association's betting rules and banned from football for eight months, until January 17th of 2024.

But it’s not just the teams at the lower end of the table that are bringing back the era of the big man. Those players are present in teams towards the top of the table also.

English football, and by extension, modern football, has largely moved away from fixed ideas. This is in no small part thanks to the systems that Manchester City and Liverpool have imposed in their pursuit of excellence. They have favoured efficiency and ruthlessness, systems over individual talent, the team as a whole rather than a single man to light the fire.

The demands of the modern game changed consequently, emphasis was placed on high-intensity sprinting, acceleration and versatility. Old-school positions fell out of favour, like the No.10, and the target man.

Guardiola was among the first to note the shifts in the game, and inspired a big part of it. Attacking midfielders, ball-playing centre-backs and flying fullbacks quickly became staples of both his and Klopp’s teams, despite the drastic difference in style between the two. Soon, both clubs had amassed a wealth of talent to the same tune.

Erling Haaland is 6 ‘4’, and his rawer counterpart, Darwin Nunez, is 6 ‘1’. Haaland converted over seventy percent of his clear-cut chances last season. Nunez, less prolific, was still his team's answer every time they needed a goal. Football’s industry has wasted no time in pigeonholing the two as classical centre-forwards. And that is what they look like.

But looks can often be deceiving. A Korean Youtuber recounts his experience of seeing Haaland live at Dortmund’s Signal Iduna Park, “Oh fuck, he’s fast–he is too big to be that fucking fast”. Haaland isn’t your classic big man, he accelerates and hits top speed in no time. A tall forward running towards you at top speed is a sight to behold. In fact, to many who have followed him, his speed, not his finishing, is his strongest attribute.

Haaland knows that City have signed him to lurk around up front and score goals. It’s in Guardiola’s plans for him to touch the ball the least (22.05 times per 90, in the 3rd percentile of all positional peers in the top 5 leagues) out of anyone in the team. But he is a forward who offers much more than that, he can drift out wide and knows how to drop deep and lay off the ball.

Nunez is much the same at Liverpool. Gangly, tall and awkward, he fits the target man stereotype even more than Haaland does. But to anyone who has watched Nunez play, beyond highlight reels, knows that he rarely ever plays the classic part. Nunez is an agent of chaos, Four Loko in human form.

For Jurgen Klopp, who prioritises the seamless movement of his forwards, that has clearly been the over-arching reason why Liverpool decided to forego their usual thriftiness and spend 100 million on Nunez.

A popular meme when Nunez signed was of Bart Simpson jumping through a window head first, hinting that Nunez had been signed to do little else except jump on the end of every ball played in by Liverpool’s passer extraordinaire, Trent Alexander-Arnold. The truth, as usual, is some way off. Nunez is rarely in those positions, and rightly so.

Neither of the two big money forwards conform to the idea of the ‘traditional’ center-forward, they are as nimble-footed and canny as their modern attacking counterparts. The media and the fans can be forgiven for mistaking them, but the really terrifying thing lies in the fact that both of them can serve multiple roles.

Manchester City and Liverpool are not regressing by returning to the mean of centre-forwards. They are reinventing the position, even as they bring it back. Chelsea tried to replicate the old with Romelu Lukaku, but as an all-timer bag fumbler, Lukaku made sure that experiment quickly failed. Wout Weghorst was brought into Manchester United last year to be that traditional Target Man up top, but they found out that you can drag a Weghorst to the goals but you can’t make him score.

Haaland and Nunez are here to entertain, not simply serve a role in finely tuned systems that already lead the goal-scoring charts. The teams are simultaneously built around them, while also being functional without them. It’s all led to a revolution at the #9 position that we are fully in the midst of currently.

Conclusion

“Give it to the big man and let him dominate” ~ Shaquille O’Neal

Any centre-half who played in England in the 1980s will tell you that the real meaning of hell is spending 90 minutes lined up opposite a man called Billy Whitehurst. A somewhat limited technician and unsentimental soul who was once described as looking like “Frankenstein’s monster”, by himself, Whitehurst has a case for being the most terrifying footballer ever to roam the green (or wet brown with speckled green as it mostly was in his day). A story told about him stated that he once challenged the entire Crystal Palace team and staff to a fight and honestly - given that he apparently was an avid bare knuckle boxer - my money would’ve been on big Billy.

During a short spell at Sheffield United (Wikipedia says he played for 23 different clubs in his journeyman career), the manager, Dave Bassett, reportedly gave Whitehurst a simple pre-match instruction: “Go and cause some bollocks, Billy.”

Such hi-jinks are no longer part of top-level football, now that casual GBH has been identified as a red-card offence, but I can’t help but see the same instructions being given to this new generation of strikers, especially the Uruguayan upheaval machine that we call “Darwin”. Truly it is fitting that he was amongst those chosen to evolve this role for the modern era.

That being said, even though the position has been somewhat revolutionised, that doesn’t mean the old classic styling has no place in the game. I’ll always remember the moment when Louis van Gaal sent on Luuk de Jong and Wout Weghorst (combined height 12 feet 6 inches) to cause some bollocks in the World Cup quarter-final against Argentina.

Weghorst scored twice to take the game to extra time, and for a while Argentina’s defenders looked like they’d been the focus of a skill robbery on the scale of Space Jam (with Papu Gomez playing Muggsy Bogues, obviously).

After a bunch of fights and pettiness, eventually Argentina won on penalties and Lionel Messi found his head somewhere on Mars after he called Weghorst an idiot after the game. It was truly a glorious moment for modern football.

When even the country that invented Total Football can see the benefit of just chucking it up to the big lad and seeing what happens can bring to the game, especially in an era where there’s sucha deep focus on every tactical aspect of the game, it really brings this sport we love so dearly back down to its fundamentals.

And you can’t spell “fundamental” without “fun” and “mental”.