Making the Case - Johan Cruyff

Football is a special game.

The closeness of the fans to the pitch, for the most part, gives fans one of the most intimate experiences of a team sport that exists, and because of the vastly different positions and styles, Football allows for players and teams develop their own distinct identities and signature styles through their creativity flair and athleticism.

Each club is deeply linked to the area in which it is based, and takes on the characteristics and identities of the fans they represent out on the pitch. Those fans, in return, pour their lives into the club.

While the game has changed significantly in recent times thanks to the huge amounts of money being poured in at the top levels, below those sections the game is still as it once was.

Players are constantly compared to their peers and to the legends of the past in order to answer the most hotly contested question in the sport:

Who's the greatest football player of all-time?

Modern era fans will tell you it’s Messi or Ronaldo. Older fans will espouse the virtues of Pelé and Maradona. If you were compiling a list of players that many would place on their personal Mount Rushmore’s, they’d be the obvious answers.

For many the question is redundant. They believe in only one correct grouping of answers. Their ones. Others might have their own personal stance but acknowledge one or two alternatives.

I believe that there's much more nuance to the question of greatness.

I’m a fan of the less obvious choices. The icons that could have been. Those that often fly under the radar in these arguments. The legends who left a mark on the game that’s so significant, it ripples through time. Those that embedded themselves into the game. Those that *became* Football.

It's a subjective thing though. I can't give you a definitive answer. All I can do is make an argument. Give my opinion. Show you why I believe what I believe.

So, I’m going to be writing a series of pieces over the next couple of weeks and months about the greats of the game, and whether they deserve to be mentioned amongst the upper echelons alongside the names I’ve previously noted.

I’ve devised 4 criteria to judge each player on:

Honours

Trophies won, individual accolades (Ballon d’Or’s, PotY trophies, Top goalscorer acheivements, Team of the Season/Tournament recognitions, etc.). A Basic Breakdown.

Team Contribution

What they contributed in major games across their career.

Style

Their style of play. How their game would translate across to the modern age.

Cultural Contribution

What did they contribute to Football as a whole? How did they change the game for the better/worse?

The first two are quantitative measures. The last two are a qualitative assessment. Individual honours very much depend on where a legend played, rather than how they played, so I’ll be taking this as a more generalised section in the beginning of each piece, and only slightly taking it into account in analysing each player.

I won’t be making the decision on whether or not these players deserve to be mentioned amongst the pantheon though. That’s up to you. At the end of all this, let me know what you think in the comments, or in my Twitter replies/Quote Tweets.

Time for Part 1.

Johan Cruyff

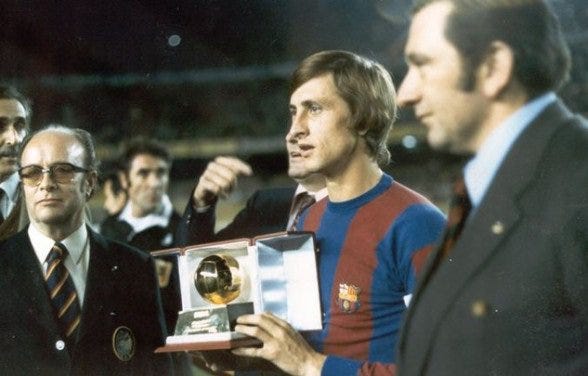

“If the 175,000 FC Barcelona members queued up in an orderly line, night after night, to massage his tired feet, cook his dinner and tuck him into bed; if they carried his golf clubs round Montanyá’s hilly 18 holes; if they devoted 50 percent of their annual salary to him … it still wouldn’t be near enough to repay the debt those who love this club owe Johan Cruyff.”

These are the words of Graham Hunter, author of Barça: The Making of the Greatest Team in the World.

Johan Cruyff is many things to many people. The Greatest Player of all time. The greatest manager of all time. The greatest all-round football orientated thinker of all time. To even be in the conversation for one of those is unbelievable. But to be a strong contender for all three is simply insane.

Let’s get this out the way first. If we’re talking numbers, Johan Cruyff is objectively not the best manager ever nor the best player ever. There are players and managers that have achieved far more than he ever did from a goals, assists and silverware perspective.

But what he did for the game extends far beyond numbers. Which is why in this scenario, the greatest and the best mean two very different things. He changed the very fabric of football in ways that simply cannot be understated and need reiterating whenever possible.

Let’s dive in.

Honours:

Hendrik Johannes "Johan" Cruyff was born on 25 April 1947 in the Burgerziekenhuis hospital in Amsterdam. He grew up just a few streets from Ajax’s stadium, joined their youth academy at 10, made his first-team debut in 1964 aged 17, and made an instant impact, scoring on his debut. He would play for Ajax for 10 seasons and score 257 goals in 329 games. In this period he won six Eredivisie titles, five KNVB Cups and, most remarkable of all, won three European Cups consecutively from 1970 to 1973. In 1972 alone Ajax won the Dutch league title, the Dutch cup, the European Cup, the European Super Cup and the Intercontinental Cup. They were simply incredible and all things being equal, would likely beat any club side on earth today.

He was transferred to Barcelona for a world-record fee and won La Liga in his first season, the club’s first title since 1960. He played five seasons in Spain and then promptly retired aged just 31. But after losing a lot of money in pig farming – yes, pig farming – he came out of retirement and played for the Los Angeles Aztecs and Washington Diplomats before returning to the Spanish second tier to play for Levante for a season, then returned to Ajax for two campaigns, two league titles and a cup win. There was a major fallout, he felt betrayed and he then joined rivals Feyenoord as an act of revenge for one season, and promptly won the league and cup double with them.

At this point, having played 702 games and scoring 402 times, and having won three Ballon d’Ors in 1971, 1973, and 1974, he retired for good.

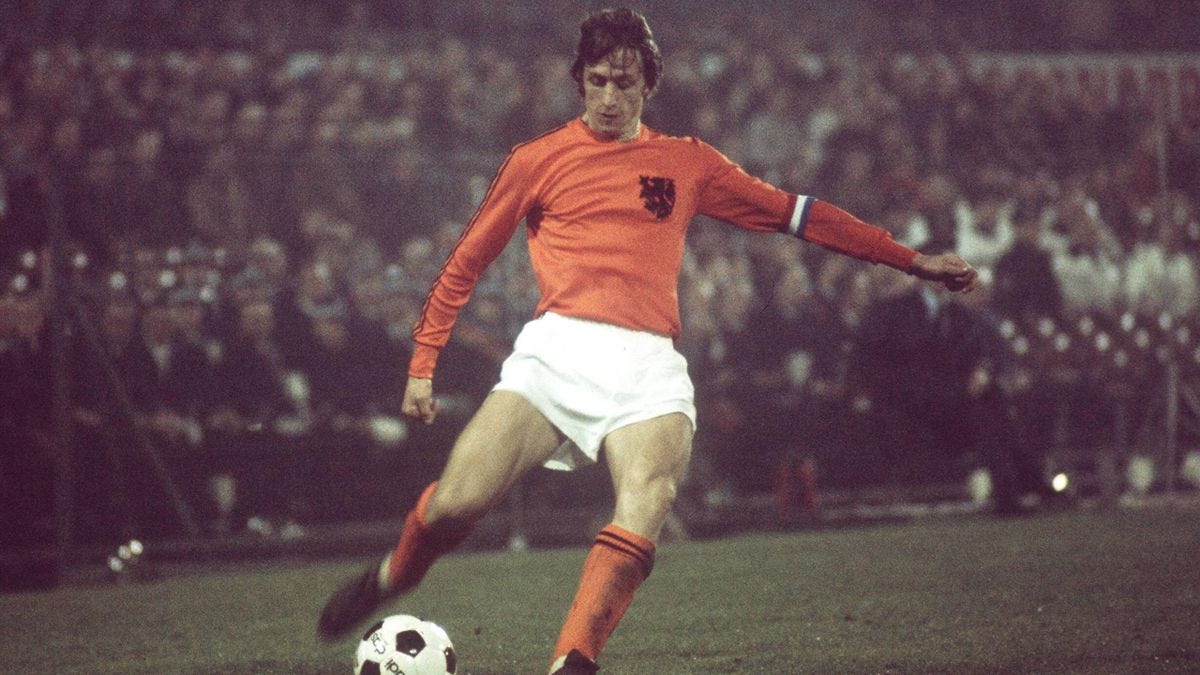

His international career numbers of 33 goals in 48 games only hinted at the profound effect his Dutch side had on world football, especially in the 1974 World Cup, in a final played out in stair rods of rain in and against West Germany. They remain the greatest side not to win the World Cup. It was at this tournament that we saw the Cruyff turn for the first time, likely Cruyff’s most iconic moment, and most certainly the way most people nowadays would know of him, but the world already knew of Johan Cruyff and Ajax from TV broadcasts of their European Cup adventures.

But the story was only just starting for him, as he began a legendary- if short - managerial career, starting with a 30-month stay at Ajax and a 72% win rate. He won two domestic cups and the European Cup Winners’ Cup in 1986/87. In 1988 he took over at Barcelona and in an eight-year career won La Liga for four years on the run from 1990 to 1994, the Copa del Rey in 1990, the Supercopa de España in 1991, 1992 and 1994, the European Cup in 1992, UEFA Cup Winners’ Cup in 1989 and the UEFA Super Cup in 1992.

Team Contribution

When Ajax reached the European Cup final in the 1970/71 season, they were established as one of the best teams on the continent. Manager Rinus Michels had been in charge for six years, a 24-year-old Cruyff had been in the side for seven, and they'd won several Eredivisie titles and domestic cup trophies as well as reaching the European Cup final just two years earlier (losing 4-1 to AC Milan).

Hoping to stop Ajax from winning a first European Cup were Greek champions Panathinaikos, managed by Ferenc Puskás. But they were powerless to stop Cruyff and Ajax. Within five minutes of kick-off, Dick van Dijk headed home Piet Keizer's near-post cross from the left and Ajax never looked back.

Panathinaikos struggled to contain Cruyff, who completed 13/15 dribbles playing in a very advanced left-wing role, with van Dijk playing as the 'False 9', charged with dropping in and progressing the ball to the final third. Late in the match, Cruyff set up Arie Haan with a trademark mazy dribble and deft throughball to secure the first of Ajax's three consecutive European Cup triumphs.

Rinus Michels departed Ajax for Barcelona in the summer of 1971, so Ștefan Kovács would lead Ajax to their second European Cup final, this time against Inter Milan. Both Cruyff and Ajax excelled in 71/72 under Kovács' tutelage: Cruyff won his first Ballon d'Or at the end of 1971, and Ajax had a perfect home record in the league, suffering just one defeat in the entire season and winning both the Eredivisie and the KNVB cup. A European Cup win would secure the treble.

This game holds a significant place in the footballing tapestry as it's seen as the death of Catenaccio, with the torch passed to Ajax's Total Football. Ajax dominated the game, with Cruyff – scoring both goals in the False 9 role – and teammates rotating and interchanging relentlessly to find openings inside the Inter defensive block. Cruyff's desire to hunt for space, and his ability to spin his defender and carry the ball into dangerous areas, were particularly evident in this game.

In the summer of 1973, Barcelona parted with a then-world record fee to bring Cruyff to the Camp Nou and reunite him with manager Rinus Michels. Cruyff slotted straight in as the False 9 in Michels' preferred 4-3-3 and contributed 16 goals as he helped Barça to their first La Liga title in 14 years. Cruyff's continued excellence won him his second Ballon d'Or at the end of 1973.

In February, they faced arch-rivals Real Madrid in the 2nd El Classico of the season. Barcelona were 1st in the table coming into the game, with Real in 7th, and the difference in class between the two teams was glaring. Barça ran out 5-0 winners in one of the most iconic El Classicos of all time – with Cruyff putting in one of his greatest-ever performances.

His goal – Barcelona's 2nd – displayed the close control and quick feet that made him untouchable as a dribbler. Within four seconds in the first half, Cruyff received the ball on the edge of the Real box, deftly skipped past two defenders, shrugged off another, and then calmly stroked the ball beyond the goalkeeper.

Cruyff drove Barcelona to this victory. He applied more pressures (19) than any of his teammates and received the ball all over the pitch, showing the bravery and craft to drop into wherever he felt he could affect the game.

A big point that stands against Johan Cruyff as a all-time great of the game is that he only competed in one World Cup. But good lord, what a World Cup. One that can be defined by his true introduction to world football.

24th minute. Holland vs Sweden. Once again in the False 9 role, Cruyff receives the ball on the left flank and stands up Swedish fullback Jan Olsson. Cruyff feints to go back inside, before dragging the ball behind his standing leg to turn 180 degrees in a step that has now been seen around the world an infinite number of times: The Cruyff turn. A career-defining moment.

That aside, Cruyff had a typically influential game. He created five of the Netherlands' 30 shots and took four of them himself, but the 12 completed dribbles from 16 attempted – one in particular – stole the headlines.

The Netherlands qualified with ease. Their reward was a second group stage containing Argentina, East Germany, and Brazil (The tournament featured a new format. Sixteen teams divided into four groups of four teams, the eight teams which advanced did not enter a knockout stage, but instead played in a second group stage. The winners of the two groups in the second stage then played each other in the final).

Their first match against Argentina was arguably the Netherlands' best performance of the tournament as they took apart their more reductive opponents. The 4-0 scoreline didn't flatter the Dutch as they outshot Argentina 18-3, controlled 58% of the possession, and entered the final third 96 times, allowing Argentina to progress into the same area just 17 times.

Cruyff was influential once more, scoring twice and assisting the fourth. His first goal was another example of his ball mastery and composure, receiving the ball behind the Argentina defence and skipping around Daniel Carnevali to pass into the empty net to give the Netherlands the lead.

They struggled to create clear-cut chances vs East Germany, but did enough to come away with a 2-0 victory. By his own high standards, Cruyff was quiet in this match, registering zero shots, one key pass, and only one touch in the opposition box. The East Germans paid him close attention: 24% of Cruyff's passes in this game were played under pressure – the highest rate of any player in any game in that World Cup.

It came to the winner-takes-all match versus Brazil to decide who would advance to the final. You'd think the Netherlands versus Brazil in a 1970s World Cup semi-final would be an exhibition of technical and flamboyant football.

You'd be wrong.

A seemingly never-ending stream of dirty, and frankly dangerous, tackles ensued. Fifty-six fouls, many of them knee-high, somehow equated to only five yellow cards and one 85th-minute red.

The match itself was a close contest when the players weren't trying to cut each other in half. Brazil had their chances to win, creating 0.96 xG to the Netherlands' 0.75, but were wasteful, hitting the target with just one of their 14 shots.

Cruyff was – again - the difference maker for the Netherlands, assisting Johan Neeskens for the first goal before wrapping the game up with a majestic volley at the near post.

After six matches and an aggregate scoreline of 14-1 (including 8-0 in the second group stage), the Netherlands were the experts' favourites to win the World Cup, despite West Germany's home advantage.

And that favouritism looked justified as the Dutch took the lead after just one minute – and before the West Germans had even touched the ball. (You can watch the sequence in the video below, which I’ve synced up to the kick off)

After 40 seconds and 14 passes, the ball reached Cruyff, who'd dropped deep to become the very last man outfield. Cruyff set off on a trademark mazy dribble, accelerating through the German midfield and defensive lines before being scythed down by Uli Hoeneß as he entered the box. Johan Neeskens stepped up, converted the fastest goal ever scored in a World Cup final, and West Germany's first touches of the ball would be at 1-0 down.

However, West Germany fought back. Paul Breitner equalised with a penalty of their own before Gerd Müller broke the then-record for the most goals scored in World Cup tournaments (14) to give them a 2-1 lead.

At half-time, the shot count read West Germany 9-3 Netherlands, the West Germans succeeding in shutting Cruyff and the Dutch down, largely down to the man-marking of Berti Vogts and with the great Franz Beckenbauer, Wolfgang Overath, and Hoeneß flooding the midfield and restricting the space.

The Netherlands mounted a comeback of their own in the second half, creating 13 shots to West Germany's one, but it was to no avail.

And so the Netherlands had to settle for second best. But Cruyff would win the World Cup Golden Ball and, later in the year, his third and final Ballon d'Or for his mesmeric performances at the tournament. Indeed, Cruyff was the top performer by StatsBomb’s On-Ball Value metric in four of these five matches, a model that values each action based on the +/- impact it has on the team's likelihood of scoring and conceding.

The guy stepped up when he needed to. Cruyff was victorious just about everywhere he touched a ball. He won 80% of the Eredivisie matches he ever played in (245/308). Unsurprisingly, now six years after his death, that’s still the highest win percentage among players with 100+ appearances in Dutch top-flight history. That record may disappear one day, but Cruyff’s status as a pioneer of modern football won’t go with it.

(All stats in this section taken from, and used with the permission of Statsbomb)

Style

Cruyff is widely seen as a revolutionary figure in the history of Ajax, Barcelona, and the Netherlands. The style of play Cruyff introduced at Barcelona later came to be known as tiki-taka—characterised by short passing and movement, working the ball through various channels, and maintaining possession—which was later adopted by the Euro 2008, 2010 FIFA World Cup and Euro 2012 winning Spain national football team.

Throughout his career, Cruyff became synonymous with the playing style of "Total Football". It is a system where a player who moves out of his position is replaced by another from his team, thus allowing the team to retain their intended organizational structure. In this fluid system, no footballer is fixed in their intended outfield role. The style was honed by Ajax coach Rinus Michels, with Cruyff serving as the on-field "conductor". Space and the creation of it were central to the concept of Total Football.

Ajax defender Barry Hulshoff, who played with Cruyff, explained how the team that won the European Cup in 1971, 1972 and 1973 worked it to their advantage: "We discussed space the whole time. Cruyff always talked about where people should run, where they should stand, where they should not be moving. It was all about making space and coming into space. It is a kind of architecture on the field. We always talked about speed of ball, space and time. Where is the most space? Where is the player who has the most time? That is where we have to play the ball. Every player had to understand the whole geometry of the whole pitch and the system as a whole."

Cruyff was known for his technical ability, speed, acceleration, dribbling and vision, possessing an awareness of his teammates' positions as an attack unfolded. "Football consists of different elements: technique, tactics and stamina", he told the journalists Henk van Dorp and Frits Barend, in one of the interviews collected in their book Ajax, Barcelona, Cruyff. "There are some people who might have better technique than me, and some may be fitter than me, but the main thing is tactics. With most players, tactics are missing. You can divide tactics into insight, trust and daring. In the tactical area, I think I just have more than most other players." On the concept of technique in football, Cruyff once said: "Technique is not being able to juggle a ball 1,000 times. Anyone can do that by practising. Then you can work in the circus. Technique is passing the ball with one touch, with the right speed, at the right foot of your team mate."

Cultural Contribution

Britain had The Beatles and The Rolling Stones. The US had Elvis Presley and The Beach Boys. The Netherlands had Johan Cruyff. He was their Rockstar.

Their art forms were different but his legacy has been just as important. Cruyff was not merely the key figure in tactical revolutions in the 1960s and 70s that took them from being a football backwater to the world’s most important football nation. He changed the personality of the country, too. In an article to mark Cruyff’s 50th birthday in 1997 the Dutch writer Hubert Smeets argued that Cruyff had done more than anyone to shape the modern Netherlands.

Cruyff clashed with football authorities, inspired, astonished and delighted his contemporaries and smashed old patterns of deference. To the old “regents” who ran the country he was the voice of youth who said: “Now it’s our turn.”

Despite his long hair and aversion to those that held authority, Cruyff was no 60s Hippy. He was ferociously competitive, and thoroughly focused on money. As he pointed out: “When my career ends, I cannot go to the baker and say: ‘I’m Johan Cruyff, give me some bread.’”

In what was still the largely amateur world of Dutch football, playing for the national team was considered an honour but Cruyff demanded payment. When he discovered Dutch FA officials were paid for foreign trips, but players were not, he demanded – and forced – a change. He started asking questions that the whole generation was asking: why are things organised this way? And he never stopped.

Much like the songs of The Beatles, the Total Football that emerged at Ajax was the product of several remarkable talents provoking and inspiring each other. The coach, Rinus Michels, provided the drive, professionalism and organisational nous. Veteran Yugoslav defender Velibor Vasovic taught the callow Dutch kids how to fight and win. The doctrine of high pressing – now ubiquitous in world football, but a sensation in 1970 – derived from Johan Neeskens’ unfortunate habit of chasing opponents deep into their own half like a greyhound following a lure.

Cruyff was the essential genius behind the operation. Cruyff and Michels together re-imagined the game as a highly skilled, swirling spatial contest: whoever managed and controlled limited space on the field would win. In this, they were unconsciously drawing on wider Dutch culture. For centuries the people of the Netherlands had been finding clever ways to think about, exploit and control space in their crowded, sea-threatened land. The sensibility is apparent in the paintings of Vermeer, Saenredam and Mondrian. It is present in Dutch architecture and land management, too. It was truly just a minuscule step to make it part of their football.

Total Football swept Ajax to three successive European Cups between 1971-73, and enabled Holland to dazzle and delight the world at the 1974 World Cup. More lastingly, as Dennis Bergkamp once remarked, Cruyff’s personality and ideas shaped the entire Dutch football culture. Without Cruyff the philosophy would have died in the early 1980s, a time when most total footballers had retired and defensive football had become fashionable even in the Netherlands.

Instead, Cruyff reinstated those total principles at Ajax when he became manager. He reorganised the Ajax youth system to educate players to play his style, then repeated the trick with a bigger budget at Barcelona. We take it for granted that Spain is the land of elegant, thoughtful creative football. It was Cruyff who made it that way.

Cruyff was argumentative, arrogant, dominating and brilliant. He prized creativity over negativity, beauty, originality and attack over boring defending. Several generations of players therefore developed the same characteristics.

There were problems along the way. With his belief in the “conflict model” – the idea that you got the best out of people by provoking fights, Cruyff made enemies almost as easily as he generated delight. He went to Barcelona as a player in 1973 only because his Ajax team‑mates had insulted him by voting for Piet Keizer as their next captain. In 1983 the Ajax chairman Ton Harmsen doubted the then 36-year-old Cruyff’s ability to keep drawing the crowds. Mortified and angry, Cruyff joined Feyenoord, and promptly won them the double.

Nevertheless, no other football figure can match Cruyff’s combined achievements in his two principal careers: thrilling, mesmerising presence and performances on the field, then inspiring and hugely influential coach off it.

Even Cruyff’s blind spots and weaknesses, and awful behaviour, could lead to seismic changes to how football was played for generations to come. As he put it in one of his famous gnomic utterances: “Every disadvantage has its advantage.”

A long-running feud with The Netherlands best shot-stopping goalkeeper Jan van Beveren had started after the KNVB (Royal Dutch Football Association) decided to allocate a greater amount to Johan Cruyff, Johan Neeskens, Willem van Hanegem and Piet Keizer, leaving smaller amounts for the remaining team members. When Van Beveren found out, he informed the team. Subsequently, Cruyff pressured Michels and the KNVB to remove Van Beveren.

This led to Michels to taking Jan Jongbloed to the 1974 World Cup instead. Jongbloed was widely considered too old and eccentric but Cruyff had spotted he was good with his feet and he could roam far from goal. If he functioned almost as an auxiliary defender, Holland could press even higher up the field than usual. The concept of the sweeper-keeper was born. Without Cruyff we would never have had such brilliant modern practitioners as Manuel Neuer.

A remarkable number of the most important teams of the modern era have been directly influenced by him. Multiple eras of Barcelona and Spain, Bayern Munich and the German national teams. So did Arrigo Sacchi’s all-conquering Milan team in the late 80s (based on early 70s Ajax and featuring Cruyff proteges Ruud Gullit, Marco van Basten and Frank Rijkaard). The Arsenal Invincibles of 2003-04. The treble-winning Manchester City.

As Dutch writer Arthur van den Boogaard said, Cruyff solved the “metaphysical problem” of football. If you play a Cruyffian style well enough with sufficiently talented players it is hard to lose. He was, in effect, the father of the modern game.

So, that’s the argument.

In this writer’s humble opinion, Johan Cruyff has to be included amongst this game’s pantheon. On and off the pitch, Cruyff has contributed far more than possibly any other player to ever play the game. If you had to build a Mount Rushmore with the game’s best players on it, you’re either taking out one of the usual top four, or you’d have to find space to carve a fifth face into that sacred Native American cliff face.

The decision is yours though. Where do you think Cruyff ranks amongst the best/most influential players ever to play the game of Football?

Let me know. And tell me who you’d like me to write about next.

Thanks for reading.

Great read! A fascination with Cruyff properly ignited a love of football for me when I came across an issue of Four Four Two with him as the main cover story over a decade ago, devoured whatever interviews, books and Youtube highlights I could find. Crazy given Cruyff had effectively retired from the game many years before then.

Even if the likes of Messi can be argued as the better players in terms of talent and silverware, when everything is taken into account as you’ve done in this article it’s difficult to ignore Cruyff as the greatest bar none.